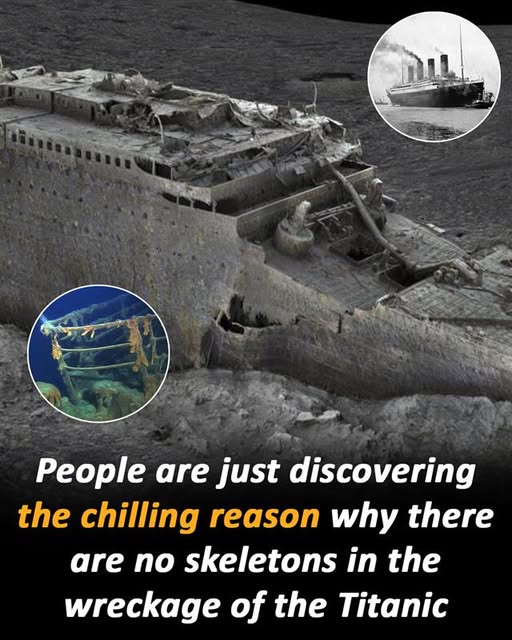

The cold truth of the Titanic’s dead is far more unsettling than the story everyone knows. People picture frozen bodies drifting through black water or lying intact on the seabed like relics suspended in time. But the ocean doesn’t work like that—not at 12,000 feet, not in a place where light never reaches and the water is cold enough to stop a heart instantly. More than 1,500 souls went into the Atlantic that night. Clothes survived. Shoes survived. The steel bones of the ship survived. But the people did not—and the reason why is equal parts science and sorrow.

When the Titanic finally came to rest on the ocean floor, the bodies that had gone down with her began to change almost immediately. At the surface, a corpse might float for a bit, carried by currents or found by rescue ships. That’s why a few hundred were recovered in the days after the sinking—pulled from the freezing water, identified if possible, buried if not. But once a body sinks past a certain depth, nature takes over in ways that most people don’t like to imagine.

The deep ocean is a place of silence and pressure, a world ruled by organisms built to consume anything that drifts down from above. Soft tissue—skin, muscle, organs—becomes food. Marine bacteria go to work first, breaking down flesh rapidly. Crabs, amphipods, and other scavengers finish the job, often in hours. The deep sea wastes nothing. Death becomes sustenance, a quiet recycling that has nothing to do with cruelty and everything to do with survival.

People sometimes ask why bones weren’t found scattered around the wreck, why rows of skeletons weren’t discovered lying where bodies fell. The answer is in the water itself. Human bones are mostly calcium carbonate. At certain depths, calcium carbonate simply cannot survive. There’s a line in the ocean called the “calcium carbonate compensation depth,” and below it, the chemistry of the water changes enough to dissolve bone. Titanic rests far beneath that line. Down there, bones don’t remain. They break down, crumble, and melt into the surrounding sediment.

That’s why the most haunting artifacts from the wreck aren’t human remains—they’re what the remains left behind. A pair of boots, still aligned as though someone sat wearing them. A coat collapsed in the shape of a torso. A child’s shoe lying on its side in a patch of silt. These objects tell a story without showing the bodies that once filled them. They’re outlines—ghostly impressions of lives erased by water, pressure, and time.

The first expeditions to the wreck were shocked by this. Some expected horrific scenes. Instead, they found absence. And it was that emptiness, that quiet, that disturbed them most. The ocean hadn’t preserved the dead—it had taken them back.

For some, knowing this adds another layer of tragedy. It underscores how utterly the sea claimed the victims. There is no underwater graveyard—no skeletal remains silently testifying to what happened. There is only the ship, slowly collapsing under its own rust, and the scattered belongings of the people who died that night.

Others find comfort in the truth. It means the victims didn’t remain trapped in a steel coffin forever. Nature, cold and impartial as it may be, drew them into itself. There is something strangely peaceful about that—the idea of bodies returning to the world the same way everything eventually does. Dust to dust, ash to ash, flesh to the ocean that swallowed them.

Artifacts from the wreck tell their own quiet stories. A suitcase that burst open, spilling letters preserved long enough to be read before disintegrating. China dishes still arranged in the sand. Glimpses of rooms frozen in time: a bathtub standing upright, a chandelier whose crystals no longer sparkle, railings twisted like paper. And in between the debris, small human touches—a hairbrush, spectacles, a child’s toy. These are the things that survived in place of the bodies.

Divers speak of a feeling you can’t shake down there. The ship sits in a world so dark that you need artificial lights to see anything. Your breath is loud inside your mask. Your heartbeat echoes in your ears. You hover over the deck where thousands once stood, hearing nothing but the hum of your equipment. The silence presses in, and the weight of the tragedy becomes almost physical.

You don’t see people. You see the spaces where they were.

The ocean doesn’t preserve the past—it absorbs it. The Titanic is rusting away, eaten by iron-eating bacteria that will eventually turn the entire ship to dust. Scientists estimate the wreck may collapse into a shapeless mound within a few decades. What was once the largest, most luxurious vessel ever built will soon be nothing more than a stain on the seafloor.

And when that happens, the only things left will be the memories carried by history. No bones. No bodies. No raw evidence of the thousands who perished. Just stories—the ones told by survivors, by descendants, by historians, and by the artifacts carefully raised to the surface over the years.

In a way, the wreck mirrors the lives it took. Nothing remains unchanged. Nothing stays intact. Everything returns to the earth, or the sea, or the silence that comes after the lights go out.

The Titanic isn’t a graveyard. It’s a place where the ocean did what the ocean always does—erase, transform, reclaim.

What persists is not the physical remains of the dead, but the memory of them. The heartbreak. The human shock of realizing that even the greatest ship in the world can sink on its first voyage. The reminders passed down through generations: stories of families torn apart, of last goodbyes on lifeboats, of musicians playing hymns as the deck tilted beneath their feet.

The ocean holds no bodies, but the world holds the tragedy.

And maybe that’s why the story endures more than any skeleton ever could.